Couple Shares Story of Living in Japanese Internment Camps

Like other Americans, Saburo Masada vividly remembers Dec. 7, 1941.

He and his family were working on a newly purchased farm in California. While taking a break, they turned on the radio to listen to a program. That program was interrupted by a news flash: Japan had bombed Pearl Harbor.

“I still remember saying, ‘What a stupid thing Japan is doing. Who do they think they are bombing our country?’” Masada said.

But within a short time, rumors circulated that Japanese Americans had something to do with the bombing — that they were loyal to Japan.

Soon, Masada would never forget another date: March 16, 1942. That day, a U.S. Army truck drove into the front yard of the Masadas’ farm. All nine family members were loaded into it and taken to the Fresno fairgrounds. Once a fun place, the fairgrounds now was surrounded with barbed wire fences and guard towers with soldiers manning guns pointed at Saburo and other Japanese Americans.

It was only the beginning.

During World War II, some 120,000 Japanese Americans and loyal permanent residents of Japanese ancestry were forcibly removed from their homes on the West Coast and taken to camps where they were imprisoned for up to four years.

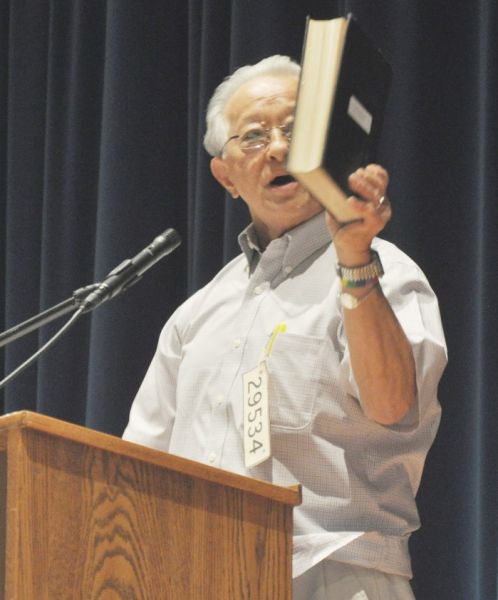

On Monday, Masada and his wife, Marion, shared their experiences in the camps with students at Wahoo High School. Students from other schools throughout the state watched via a live video feed.

The Masadas, born in California, served 43 years in the Presbyterian pastorate before retiring 17 years ago. They have spoken to clubs, churches and at schools.

They were eager to speak to students in Wahoo.

“I want them to be aware of an important part of American history which has been left out of the history books,” Saburo told the Tribune. “Most people don’t know how it could have happened or what did happen.”

Anti-Japanese sentiment actually emerged decades before the war. Saburo cited a May 1905 gathering of organizations in San Francisco to form the Asian Exclusion League to promote the anti-Japanese movement. In 1924, Congress passed the Asian Exclusion Act which prevented any further immigration from Japan to America.

Saburo attributes the forced incarceration to various factors, which included economic competition because Japanese Americans dominated the vegetable and fruit market in California. He also said there were bigots who only wanted Caucasian people in the United States.

These were but a few voices, but Japan’s bombing of Pearl Harbor provided them an opportune time to exploit fear.

Saburo said the public was duped and politicians — wanting to be elected or re-elected — backed the mass incarceration.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which authorized the incarceration, on Feb. 19, 1942.

“The government tried to say in the propaganda that it was to protect us, but the towers and the guns were pointed at us,” he said. “And you don’t protect innocent people by imprisoning them.”

Raised to obey authority, Saburo said people didn’t try to escape.

He cited an instance when a hearing impaired man was shot to death. The man, who had befriended a stray dog, was trying to retrieve the animal which had gotten past the fence.

A boy trying to get a ball that had rolled away and went to the fence was shot to death as well.

While he said the camps in which Japanese Americans were held were nothing like the German ones — those were death camps — he still calls them concentration camps.

To Masada and other children, the incarceration was traumatic. Two-thirds of the prisoners were children under age 15.

“My mother drummed it into us that we were to remember our number because ‘they will not know you by your name from now on. You are a number.’ It was a way of dehumanizing us,” she said.

She remembered the thick dust storms in Arizona. The family of eight lived in one room with no partitions. Beds were side by side. There was a community bathroom with showers for women and for men. There was one mess hall; her father was a cook and her mother a dietitian. Marion washed all the family’s clothes by hand and did the ironing. She had little time to play.

One day, a friend invited Marion and her sister to stay overnight in her barracks. In the night, that girl’s father molested Marion, who kept the incident to herself for many years.

“My whole experience in camp was a traumatic one I was made to feel that I started the war. I felt being Japanese was bad. … I felt a hurt I couldn’t explain. I didn’t know how to fight back, I would be so angry I would take it out on others,” she said.

After the war, the family discovered that their valuables, left with a landlord, had been looted.

“Even our car was an empty shell,” she said.

The family had a difficult time finding housing. No one wanted to rent to them.

She did make friends with a girl in high school, who invited her home on weekends. Marion fought tears as she told how she was loved like a member of that family.

After their talks, the Masadas answered questions from the audience, which gave them a standing ovation.

Wahoo junior Zach Gropp thanked the couple for coming and said they amazed him.

“Most people I know would not be able to do that. It’s really enlightening to know that there are people who are brave enough to share their stories,” he said.

Zach said he plans to become a teacher.

“Teach our stories. Please tell our stories, OK?” Marion asked Zach. “Don’t let our stories die.”

Zach agreed that even thought he was going to become a math teacher, he would tell their stories.

Please click HERE to view the entire assembly.

Preview Article:

WHS to Host Japanese American Internment Camp Survivors in April 23 Assembly

Masadas Share Their Experiences from Often Overlooked Historical Event

“Those who fail to learn from history are doomed to repeat it.”

Sir Winston Churchill’s famous words of wisdom drive home the importance of learning history, and the need to make sure the history we teach in our schools is accurate and complete, without being “sugar-coated.”

Most of us have no problem proclaiming that the United States is the greatest nation on earth! We definitely have many reasons to be proud and many blessings to count. Like all great nations, though, our leaders throughout history have not been flawless, and at times their decisions have produced historical events that warrant no pride; nonetheless, possessing a knowledge and understanding of these unfortunate human downfalls is very important.

On Monday, April 23, 2012, California natives Saburo and Marion Masada will address an important and tragic event in American history that often sees little to no coverage in our history textbooks: the Japanese American internment camps that were established across the Western United States in the days following Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor.

Saburo and Marion Masada

The Masadas will be featured in an assembly, which will be held April 23 at 1:00 p.m. in the WHS Performance-Learning Center. All WPS students grades 8-12 will attend, and the event will also be offered to other schools throughout the state via a live IP video feed. The public is also invited.

Marion comes from a family of ten from Salinas, California. Her mother was born nearby, and her father was an immigrant from Japan. Saburo comes from a family of nine from Fresno, California. His parents were both immigrants from Japan.

In 1942, when Marion was eight and Saburo was twelve, their families were forcefully removed from their homes and incarcerated, along with 120,000 other loyal Americans and permanent legal alien residents of Japanese ancestry living on the West Coast. Their “home” for up to the next four years was one of America’s ten concentration camps scattered in desolate areas in seven states, away from the West Coast. These camps were established under Executive Order 9066, signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Saburo’s family was imprisoned in Fresno, CA, from May 16 to October 30, 1942, and was then taken to the Jerome Concentration Camp (2 years) and Rohwer Concentration Camp (1 year) in southeastern Arkansas. Marion’s family was imprisoned in Salinas, CA, from around April 27 to July 4, and then taken to the Poston II Concentration Camp in Arizona.

“World War II began in 1941, and it’s hard to imagine that I’d be sharing our story 70 years later,” Saburo said. “Our government did not teach this part of U.S. history in our schools, and the little that was made known was not always factual. I hope Marion and I will be able to present an accurate history of what happened while we share our personal experience.”

In a 1943 Congressional Hearing, Lt. General John DeWitt, Commander of the Western Defense Command who administered the internment program, testified: “I don't want any of them [persons of Japanese ancestry] here. They are a dangerous element. There is no way to determine their loyalty... It makes no difference whether he is an American citizen, he is still a Japanese. American citizenship does not necessarily determine loyalty... But we must worry about the Japanese all the time until he is wiped off the map.”

Eventually, future leaders took note of this not-so-subtle racial prejudice, and attempted to right the wrong.

In the 1980’s Congress investigated this tragic event, and in 1988 President Ronald Reagan signed legislation which offered an apology to those interned on behalf of the U. S. Government, concluding and stating that the act was wrong, and was caused by “race prejudice, war hysteria, and failure of political leadership.”

In 1990 President George H. W. Bush sent a letter of apology with a redress check of $20,000 as a token restitution to each of the survivors still living.

This year marks the 70th Anniversary of FDR’s Executive Order 9066, signed on February 19, 1942, which authorized this tragic event. The majority of Americans know little or nothing about this event, which many consider to be the most blatant and worst blow to Constitutional liberties that American citizens have ever sustained at the hands of their own government.

In the study of history, it is important to teach the negative along with the positive, so as a nation we can continue to thrive in doing what is right, and do everything in our power to avoid repeating the wrongs. That can only be accomplished through knowledge.

The Masadas have been speaking to service clubs, schools and churches across the country to inform people of what happened, and to help ensure that such actions will never be repeated in our great nation.

Saburo and Marion served for 43 years in the pastorate of Presbyterian churches in California and Utah, and retired 17 years ago. They have three grown daughters.

Launch the media gallery 2 player

Launch the media gallery 2 player Launch the media gallery 3 player

Launch the media gallery 3 player